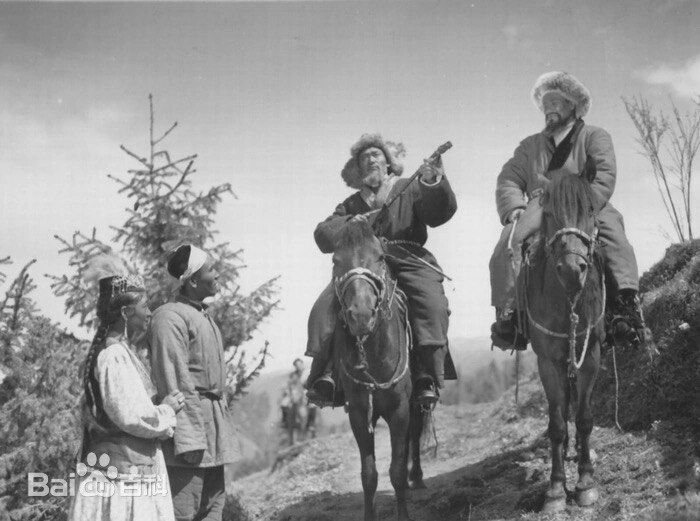

The 1955 film reflects everyday life of Kazakh nomads.

Осы мақаланың қазақша нұсқасын оқыңыз.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

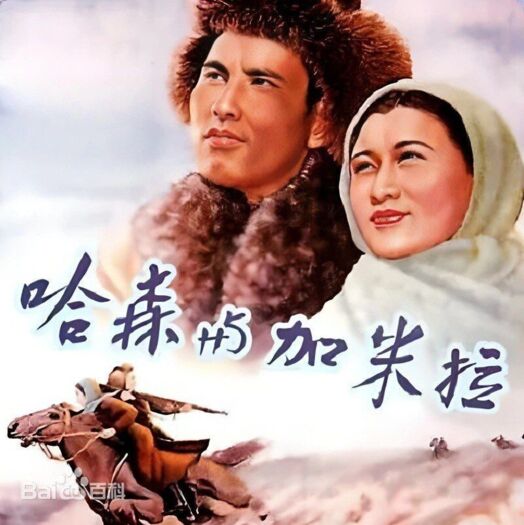

The movie “Khasen and Zhamilya” was released in China in 1955. Directed by Wu Yonggang, this film takes place in China, in today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It was not only the first to be filmed in the region but also the first to show the lives of Kazakh nomads.

Vlast spoke with experts about how Kazakhs were portrayed in the film and how it found unexpected success.

“The Fire of Love Is a Gift of Nature”

The film follows a young couple who must fight for their right to love despite external circumstances.

“Khasen and Zhamilya” was unique because it showed the everyday lives of the Kazakh people. The plot unfolds in the Ili Valley, where Kazakhs have lived for centuries.

The film opens with images of horse herds and snow-covered yurts, immersing the viewer in Kazakh culture and history, noted historian Aiganym Toleuliyeva.

“Unlike the common narratives found in Chinese films at that time, which often highlighted political conflicts, this film was created in the style of ethnic cinema,” said Toleuliyeva.

Khasen and Zhamilya live happily in an idyllic Kazakh village in China. One day, during a horse race , the son of a wealthy man falls in love with Zhamilya. On the same day, he marries her, despite her mother’s objections.

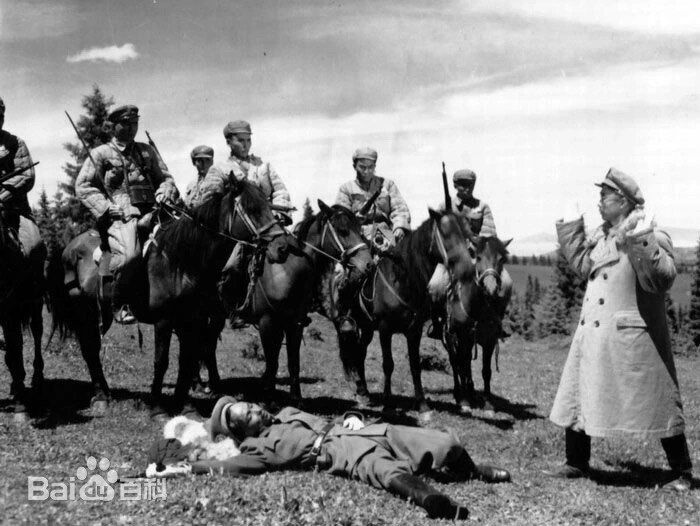

That night, Khasen kidnaps Zhamilya, and the lovers run to the mountains. Zhamilya bears their child, whom they name Makhabbat, meaning “love” in Kazakh. But soon Zhamilya’s husband wins the support of a Chinese Nationalist officer, who has the couple arrested. Later, Khasen, along with other prisoners, revolts. He escapes and joins the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) army.

At the beginning of the film, Zhamilya demonstrates her strength when she beats her future husband in a horse race. At the end of the film, she takes up arms to protect her beloved Khasen.

Toleuliyeva believes that the film’s uniqueness lies not only in the timeless love story or its strong female character but also in the beautiful presentation of Kazakh folklore.

“The film opens with a song from Khasen: ‘A golden dawn rises in the East. I’m hastening to you. Meet me like the morning rays.’ It later shows Kazakh aqyns [improvisational poets] playing the dombra [the two-stringed Kazakh national instrument]. The aqyns smile and say: ‘The fire of love is a gift of nature.’ In addition to traditional music and sports, the film shows Kazakh wedding traditions, such as fire rituals and betashar [the opening of the veil]. From the first scene you can see women in traditional clothing,” said Toleuliyeva.

“Khasen and Zhamilya” is based on a novel by Chinese writer Wang YihuIhu (1924-2008), a former secretary of the union for literature and art in Xinjiang. He also served as a deputy in the Chinese National People’s Congress.

The writer’s work was originally published in “Xinjiang Newspaper” and the magazine “Life — Reading — New Knowledge.” The novel received a positive response, and the local government of the Xinjiang district suggested that he adapt it into a screenplay.

Traces of a True Story

Bukhara Tyshkanbayev was born in the Uyghur district of the Almaty Region in Kazakhstan, but in 1916 he moved with his family to China. He studied in Ghulja and later in Urumqi. He became a poet and writer, and in 1940 he published his first poetry, short stories, and articles in newspapers and magazines.

“The movie was shown more than 12,000 times across China as well as in India and some countries in Eastern Europe.”

Tyshkanbayev helped to create the Union of Writers of Xinjiang and was selected to be one of its secretaries. His works were translated from Kazakh into Uyghur and Chinese and were published in textbooks in Urumqi and Beijing. He authored a number of plays, among which “Ghulja” (1945) and “National Strength” (1952). Before the Revolution, the Chinese Nationalist government had arrested Tyshkanbayev for his communist propaganda. This later became the basis for one of the major turning points in “Khasen and Zhamilya.”

In 1962 he returned to Almaty.

Wu Yonggang: From Shanghai to Xinjiang

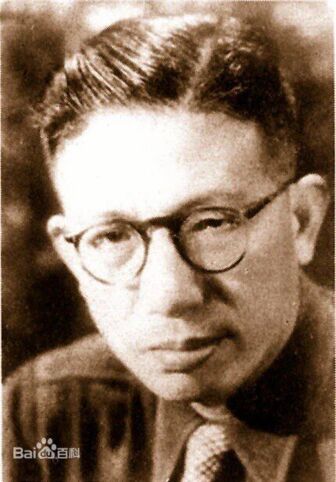

Wu Yonggang was one of China’s most celebrated filmmakers.

He grew up during a period of political instability. In 1924 Wu was expelled from school for his participation in radical leftist activity. In 1925 he became an apprentice at the Shanghai film studio “Baihe” and later became a set designer. He enrolled in the Shanghai Art School, combining his studies and profession.

In 1934 he made his directorial debut with the silent film “The Goddess,” which became a classic of Chinese cinema.

Scholar of Chinese arts at the Center of Eastern Cultures in Saint Petersburg Maria Frolova regularly lectures on Chinese cinema and runs a Telegram channel dedicated to cultural theory in film. She spoke about the work of Wu Yonggang and explained why he so drastically changed his artistic direction, making a film about ethnic minorities.

“In the 1930s, when Wu Yonggang’s artistic journey began, films tended to be socially-oriented, that is, they depicted the most vulnerable people: underprivileged girls, poor old ladies — most often the main heroines were women from disadvantaged social backgrounds. Wu Yonggang’s ‘The Goddess’ fits well into this category. Moreover, ‘The Goddess’ was very progressive for its time because it told the story of a prostitute, which was quite unusual in those days,” explained Frolova.

But why was a film about Kazakhs in Xinjiang made in a Shanghai film studio? Toleuliyeva says that Xinjiang did not have its own film studio at the time. Local studio “Tanirtau Film Studio” only opened in 1959, four years after “Khasen and Zhamilya” was released.

Shanghai was the center of Chinese cinema at the time. Wu Yonggang filmed his most notable works in collaboration with the Lianhua Film Company, one of the largest, most advanced and best-known movie studios of the time.

“The Goddess was very progressive for its time.”

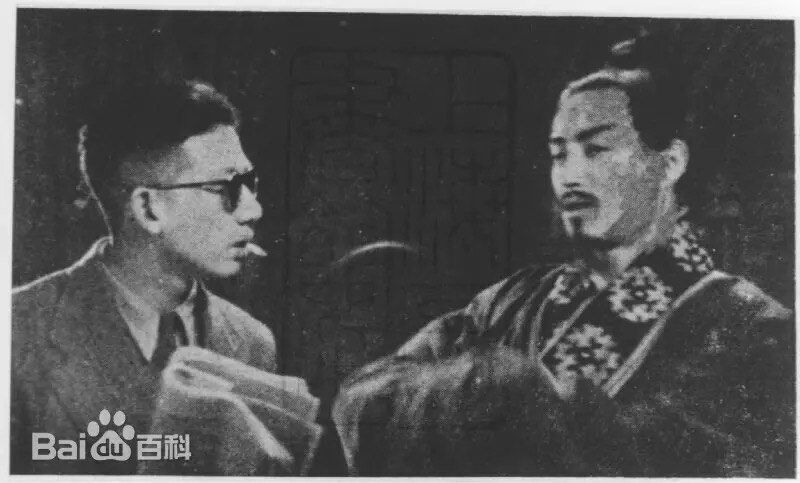

“During casting Wu decided that ethnic Kazakhs would play the main roles. When travelling to Xinjiang, he noticed student Abylai Tugelbayev, who would play Khasen, as well as translator Farida Sharipova, who played Zhamilya. They had no acting experience, so they had to learn all the basics from scratch,” said Toleuliyeva.

Wu personally coached the novice actors. In his memoir, Tugelbayev writes that, upon arrival in Urumqi, he joined a three-month acting course, where Farida Sharipova was working as a translator in a separate course for women.

“Wu Yonggang went into Kazakh villages and decided to make a film. He sought talented young men and women for the project. He gathered around 30 people. I expressed a desire to play Khasen, assuring that I could handle the lead. I told him that I could sing folk songs, ride a horse, and shoot a bow. I have all the skills that a real Kazakh man should have,” Tugelbayev wrote.

Filming on location began in June 1954. According to Toleuliyeva, harsh weather conditions repeatedly stalled the process, and the crew returned to Shanghai in the fall to work on interior scenes. Production of the movie, originally recorded in Kazakh, was completed in March 1955.

“The film premiered in Urumqi on August 1, 1955. The premiere coincided with the Eid al-Adha holiday. Over 22,000 tickets were sold the day before. In total, the movie was shown more than 12,000 times across China as well as in India and some countries in Eastern Europe,” Toleuliyeva said.

Journalist Sergey Leskovsky noted that the film was also shown on Soviet screens. It was dubbed by Gorky Film Studio, with actress Danuta Stolyarskaya voicing Zhamilya.

The film received the third prize from the Chinese ministry of culture for best artistic film from 1949–1955, as well as a memorial prize at the first Film Festival on Ethnic Minorities.

Frolova said that from the start of the 1950s, the Chinese ministry of culture began strictly controlling all aspects of the film industry. They organized a political campaign aimed at conveying CCP values to ethnic minorities.

“But it’s not necessarily explicit revolutionary propaganda,” Frolova explains. “They tried to enliven the films and make them more interesting. They produced many comedies, romantic dramas, and musicals. Naturally, they all had a happy ending and a positive depiction of communists.”

“The second goal was to show that the CCP cares for people of all ethnicities in the country and strives to unify them. Posters at the time reflected this idea: leaders of different ethnic groups were often depicted together as symbols of China’s unity and multinationality,” said Frolova.

Wu Yonggang continued to work in the film industry even into old age. In 1981 he released his final film “Evening Rain,” which was received warmly by audiences and gained several awards.

“The parents were so moved by the film that they decided to name their son after the main characters.”

Leaving a Mark

Wu Yonggang had the rare gift of discovering new talent. One of these talents was Farida Sharipova. Today she is well-known for her prolific theatrical career, memorable roles in film, and her Kazakh-language dubbing of foreign films. In 1980, she was named People’s Artist of the Soviet Union. She married Idris Nogajbayev, who won the same award two years after her.

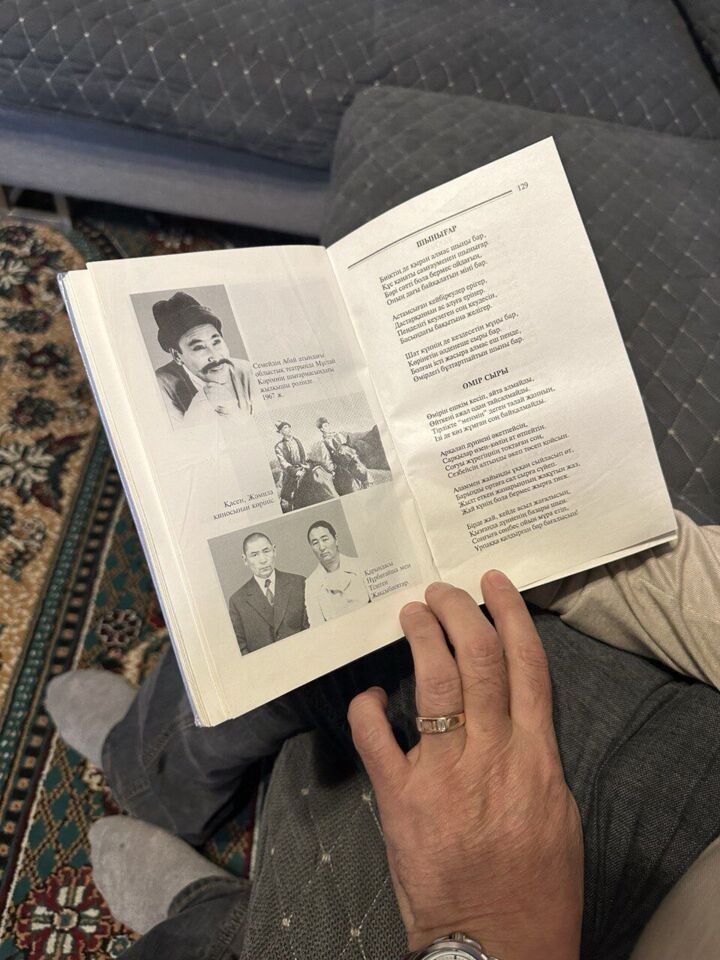

Less is known about Abylai Tugelbayev, who played Khasen. We met with his son, Marat Tugelbayev, who is also an artist and lives in Pavlodar. Marat said that his father had a multifaceted personality. He worked in the county of Ghulja in the local theater and studied in the theatrical academy in Harbin, China. His mother also took part in “Khasen and Zhamilya” as an extra. Marat’s parents worked in the Ghulja theater until 1956, when they decided to return to their homeland. After spending two years in the eastern town of Ayagoz, where Marat was born, the family moved to the nearby city of Semipalatinsk. There Abylai Tugelbayev worked in the Abai Theater.

“We were always on tour. At five, I was invited to the theater. Baiten Omarov was there. He had been in many films, but his best-known role was the doctor Badmayev in ‘Agony’ [Sergey Klimov’s 1981 film]. Omarov asked me: ‘Don’t you want to be in the show?’ I remember that next to the Abai Theater was the ‘Rodina’ movie theater where they sold ice cream. I told him, ‘only if you buy me two scoops,’” Marat laughed.

Abylai Tugelbayev worked in the Semipalatinsk theater until 1969, when he moved to the local Philharmonic.

“My dad always had a good voice. He sang, played traditional songs on the dombra, composed music, and wrote poetry. You remember the beginning of the movie when Khasen comes down from the mountains? He wrote that song himself. Even before working with the Philharmonic, the theater staged concerts after each performance. My father sang and played music while my mother danced,” Marat shares.

In 1975 the couple separated. Abylai moved to Alma-Ata (today’s Almaty) and married the poet Marfuga Aitkhozhina. He worked for some time at the Kazakhfilm studio until later becoming the director of the Ykhlas Museum of Folk Instruments, where he worked for the rest of his life. He also continued writing, developing a three-volume collection of his own poetry.

Marat has witnessed how “Khasen and Zhamilya” touched the lives of several people.

“Two years ago, I met a man whose name was Makhabbat. I said, ‘That’s a strange name for a man.’ He told me that there once was a showing of the movie ‘Khasen and Zhamilya’ in his village. His mother was pregnant at the time. His parents were so moved by the film that they decided to name their son after the main characters’ child. I was proud that even one person remembered this film,” said Marat.

The Soft Power of Cinema

In 2024 the Chinese TV series “To the Wonder” debuted at the Cannes Series Film Festival Like “Khasen and Zhamilya,” “To the Wonder” depicts the everyday lives of Kazakh nomads. Toleuliyeva believes that both the 1955 film and the 2024 series trace changes in the everyday lives of Kazakhs within the context of China’s development and the impact of globalization.

“After ‘Khasen and Zhamilya,’ Chinese studios released several other films about Kazakhs which also illustrated their life and culture. They did not become as popular abroad. I think this is because the storylines were similar, and Chinese cinema only became popular in Kazakhstan more recently,” said Toleuliyeva.

Toleuliyeva says that you should never underestimate the “soft power” of film. She believes that audiences will become better acquainted with Kazakh and Chinese cultures through joint media projects between the two countries.

This “soft power” has political ramifications as well.

“If you look at the most recent news, in 2024 President [Kassym-Jomart] Tokayev hosted Erkin Tuniyaz, the deputy secretary of the CCP Xinjiang Committee. Now Kazakhstan is collaborating with Xinjiang on several fronts: trade, industry, transportation, logistics, agriculture, and tourism,” Toleuliyeva added.

But what role does “Khasen and Zhamilya” play in a cultural, historical, and political context?

“As a historian, I think this film well reflects the reality of that time: Kazakhs, like other nations in China, became witnesses to the civil war. The movie also shows how the political situation directly impacted the relationship of a young couple. The film shows in detail Kazakh traditions [in China] which in 1953–1955 hardly differed from those in Kazakhstan,” said Toleuliyeva.

Marat Tugelbayev notes that there were few Kazakh films of that artistic caliber at the time.

“Even the first Kazakh film “Amangeldy” (1939) is overly propagandistic. But in ‘Khasen and Zhamilya’ the life of the Kazakh people is more or less believably shown. It looks fairly realistic. Later, when they made other films, the strong Soviet influence became noticeable,” said Marat.

An edited version of this article was translated into English by Zeina Nassif.

Власть — это независимое медиа в Казахстане.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.

Мы верим, что справедливое общество невозможно построить без независимой журналистики и достоверной информации. Наша редакция работает над тем чтобы правда была доступна для наших читателей на фоне большой волны фейков, манипуляций и пропаганды. Поддержите Власть.

Поддержать Власть